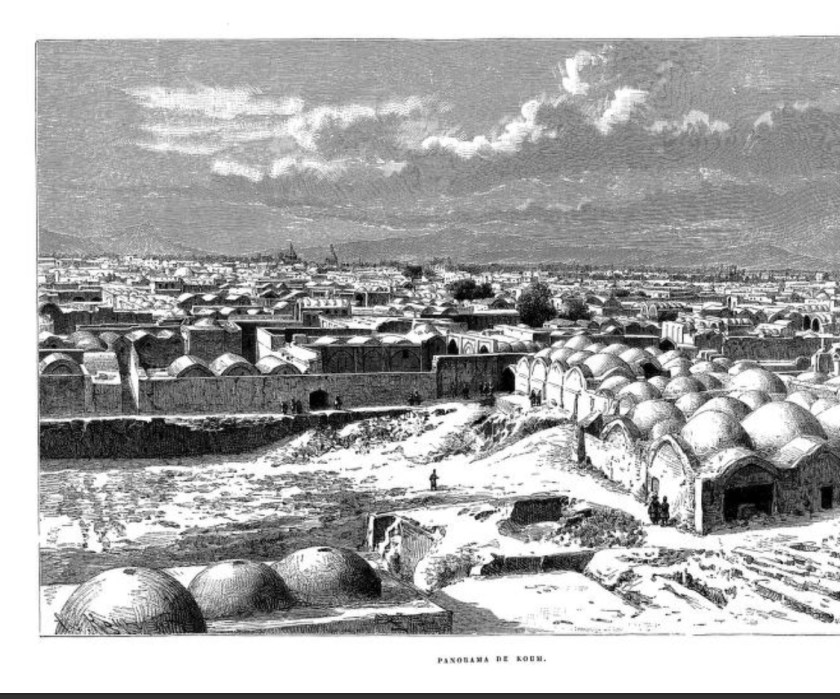

You don’t know, because it was taken long before you were born.

Your father, your grandfather, ditto.

Your child will know less, her child lesser still, what’s been lost.

Someday she might try to dig it up, maybe because life no longer makes sense to her.

In confusion and rejection of the dystopian present she senses roots calling from the past, something deeper was once here, something grander, was it an alignment, a race, an epoch, antiquitech, infrastructure, what?

What’s been lost? Where has it gone? Who took it?

Who continues to take it?

A new series for Kensho,

Starting now . . .

What does ancient Persia and modern Texas have in common? The Ice House.

If I said that to a Texan they’d think I meant the popular outdoor beer gardens, and their version of history would go back to the early 1900s and they’d think that was old. Perhaps they’d offer some local trivia or home-spun yarns, like the original Texas Ice House was the first ice manufacturing company, which is now claimed to be have been merely an ice storage facility, which later became the modern day 7-11 francise. There is, like most home-spun yarns, some truth in that story. And much redirection and fabrication as well. Perhaps to keep your eyes of our own ancient history.

More from Wiki:

In some parts of Texas, especially from San Antonio and the Texas Hill Country down to the Mexican border, ice houses functioned as open-air bars, with the word “icehouse” becoming a colloquialism for an establishment that derives the majority of its income from the sale of cold beer.[24] The distinction between South Texas ice houses and ice houses of other parts of the state and the South has been connected to the Catholicism of the region, a deeper-rooted Mexican culture, and the influence of German immigrants.

On radiative cooling

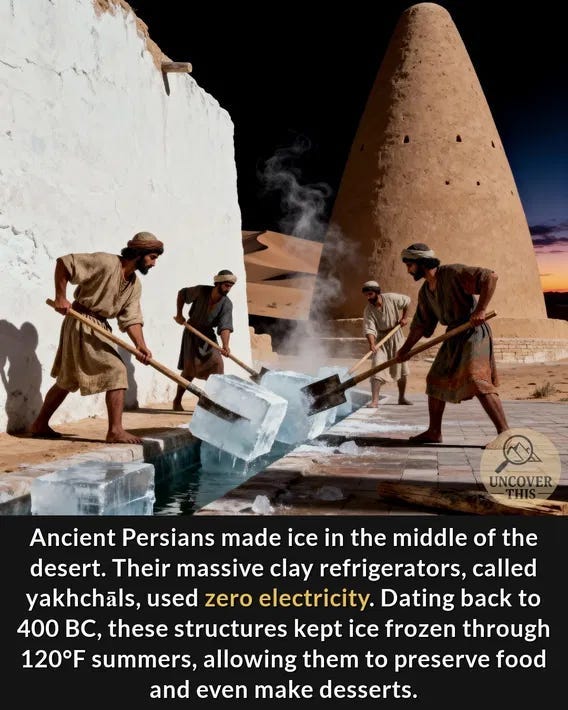

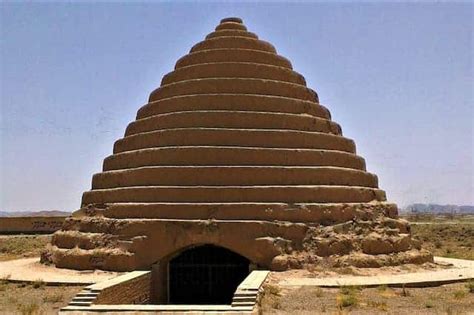

I believe it begins in Persia, still home to many ice houses, called Yakhchal. Alternative energy in the modern Western sense is really ugly, cumbersome, expensive, destructive, in comparison. Yet, there is evidence that the Yakhchal was once more widespread than just in the ancient, or modern, middle east.

The yakhchal is used for preserving and storing food, cooling structures, even making icy sweets. It works through radiative cooling, which existed in ancient times, still is in existence in remote areas today, and yet, it’s not the norm here, in the modern and advanced industrial West. Why?

That they propose it now to cool the entire planet with this line of tech means they think they can scale it that far up, yet they can’t manage to scale it back down, again. How can that be?

Geoengineering the planet with ‘lost’ radiative cooling technology, Science Direct. And ‘global radiative sky cooling’.

What is the difference between the common springhouse and an icehouse, which is the Yakhchal? My neighbors once had a springhouse, but I’d only know that because he told me himself, before he died, at over 90 years old.

Where else would such useful information be kept, I wonder? How will the next owners know there was once a springhouse there, one that might even be restored to a functioning status, when I see on their real estate listing that not even the grandchildren seem to know or care about this old feature? Who cares now, right, because we have the water co-op and the electric company we can pay each month.

I believe a case could be made that the very common structures once known as springhouses were the vernacular equivalent of the ice house.

Three main types of Yakhchals exist: vaulted, underground, and roofless, each adapted to different climatic conditions.

Passive cooling so common and effortless that even poor people could afford ice:

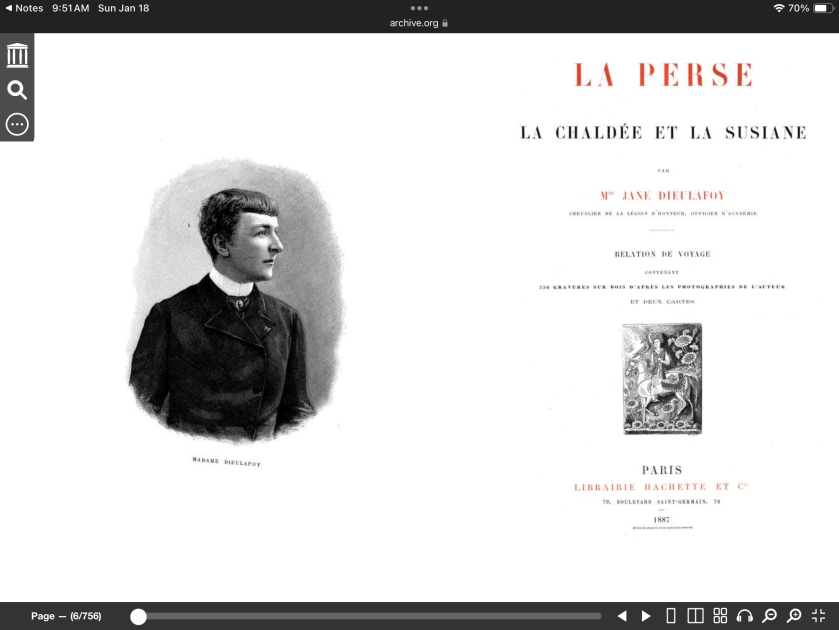

(PDF) Yakhchal; Climate Responsive Persian Traditional Architecture

Mehdipour, Armin. Yakhchal; Climate Responsive Persian Traditional Architecture.

Yakhchāl – Wikipedia

The Mughal emperors also recorded to adopt the technology of Yakchal. Humayun (r. 1530–1540, 1555–1556) expanded ice imports from Kashmir to Delhi and Agra, insulating blocks with straw and saltpetre to slow melting, a Persian technique. Early Baraf Khana (underground pits) stored ice, adapted from ‘yakhchāl’ for preservation.[4] Akbar (r. 1556–1605) organized ice transport from Kashmir to Delhi, Agra, and Lahore via a 14-stage relay system, delivering ice in two days using saltpetre. The ab-dar khana at Fatehpur Sikri used sandstone cisterns and qanats, resembling yakhchāl, to cool water and make sherbets and early desserts.[5] During the era of Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri describes baraf khana as insulated cellars storing ice for palace cooling, food preservation, and kulfi, a frozen milk dessert with pistachios and saffron. Ice was harvested in Lahore from shallow ice pans and stored in straw-lined pits.Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658).[6] Shah Jahan built a baraf khana in Sirmaur to supply Agra and Delhi’s Red Fort. These underground structures with thick walls stored ice for drinks, food, and kulfi, symbolizing imperial luxury.[7]

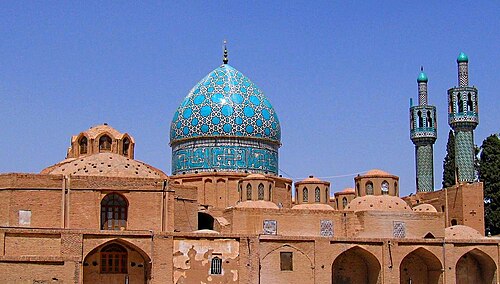

Although many have deteriorated over the years due to widespread commercial refrigeration technology, some interest in them has been revived as a source of inspiration in low-energy housing design and sustainable architecture.[8] And some, like a yakhchāl in Kerman (over a mile above sea level), have been well-preserved. These still have their cone-shaped, eighteen meter high building, massive insulation, and continuous cooling waters that spiral down its side and keep the ice frozen throughout the summer.

What we see as far as typical architectural features of the Yakhchal are domes, sometimes occuring with minerets, or spires, and sometimes with bells associated as well. Underground gardens are also a feature in the more elaborate designs.

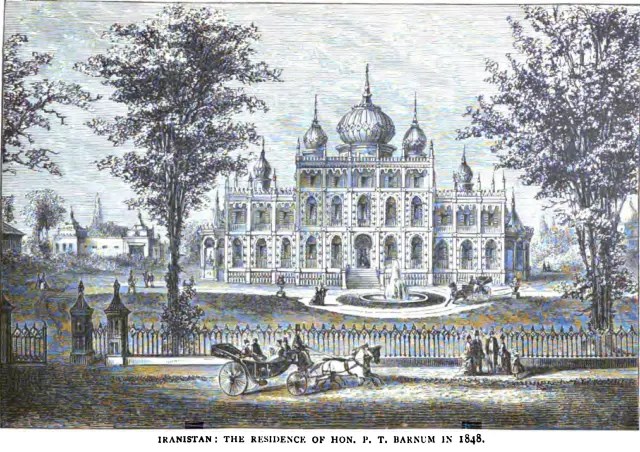

Interestingly, Dallas has such an architectural gem, though I’ve not found any mention of the yakhchal or ice house technology mentioned in the literature.

From Wiki:

Thanks-Giving Square – Wikipedia

The Square is set fifteen feet below ground level with a four-foot wall blocking the sight of automobiles to create a serene, green island. Water plays a prominent role in the landscape, with active fountains masking city noise.

Sitting amid the steel and glass skyscrapers of the Dallas business district, Thanks-Giving Chapel’s white spiral building is a beautiful—and unusual—sight. A curvilinear chapel resembling the 9th century Al-Malwia (snail shell) freestanding minaret of the Great Mosque of Samarra, Iraq, built by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mutawakkil, is not a building a visitor to Dallas expects to see. Another pleasant surprise is the Qur’anic verse “Grateful praise is due to God alone, the Lord and Nourisher of the worlds” engraved on a granite column at the entrance to Thanks-Giving Square. A portion of Psalms 100 appears on the Wall of Praise, also at the square’s entrance.

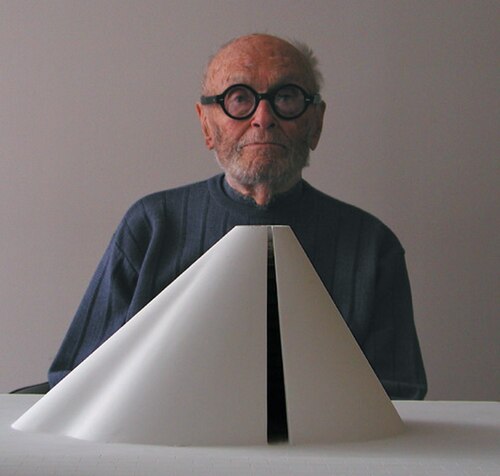

In 1971, the Dallas-based nonsectarian Thanks-Giving Foundation hired renowned American architect Philip Johnson to design a chapel that would celebrate the value and spirit of the institution of thanksgiving. Completed in 1976, Johnson’s white marble aggregate building dominates the three-acre triangular site that is dedicated to spiritual reflection. A sloping bridge built over a cascading waterfall connects the courtyard to the chapel. From his study of art history, Johnson was inspired by the spiral form of the Samarra minaret—which is similarly connected to the Great Mosque by a bridge.

“The spiral design perfectly conveys the foundation’s dual mission of offering a place for all people to give thanks to our creator and celebrating the value and spirit of thanksgiving for both sacred and secular cultures throughout the world,” Tatiana Androsov, Thanks-Giving Square’s president and executive director, told the Washington Report on Middle East Affairs.

Inside the chapel, a visitor’s attention is immediately drawn to the Glory Window (above), a multi-colored stained glass ceiling created by Gabriel Loire. This striking creation was memorialized in a United Nations stamp in 2000, the International Year of Thanksgiving. In one area of the room is a large white Carrara marble cube mounted on a sandstone circle made of local Austin stone. The cube is symbolic of the unification of mankind; the circle symbolizes eternity.

During the week, the chapel is a convenient and tranquil location in an otherwise busy city for Muslims working in the downtown business district to pray. “Although there are 22 mosques in the Dallas area, many Muslims working in this part of town like to come here, especially for Friday prayers,” Androsov explained.

Visitors from Europe, the Middle East, Asia and Africa come to the chapel as part of the U.S. State Department’s International Visitor Leadership Program, she added. The Thanks-Giving Foundation is a Department of Public Information NGO with the United Nations. For more information, visit www.thanksgiving.org.

Thanks for joining me on this little journey through time and space!

One last deep speculation–could this ancient architectural tech also relate to the so-called Mound Builder indigenous tribes all over the Americas?